Belonging

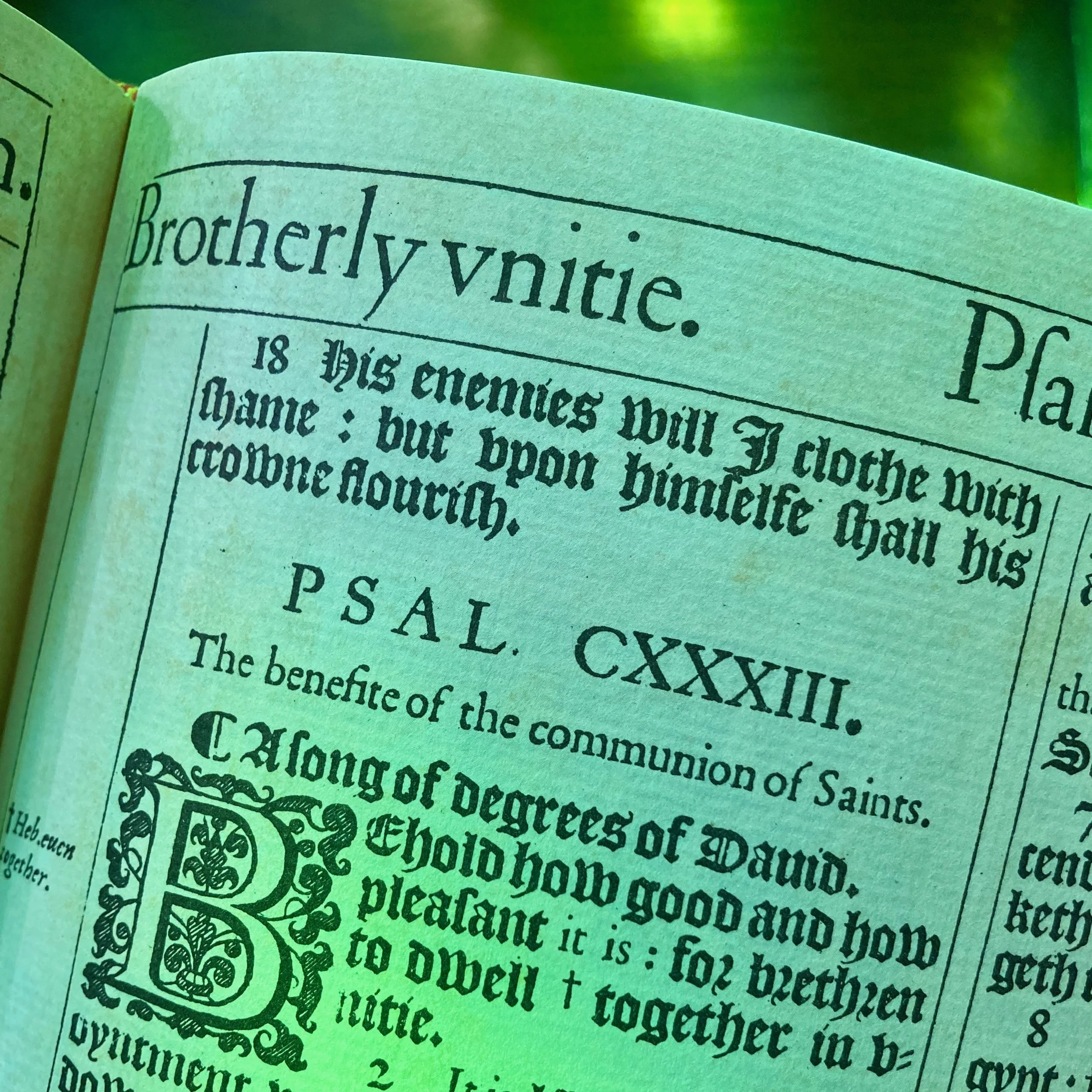

page detail from Psalms, 1611 KJV Bible (Replica Edition) photo by jch

Sermon Series “Through the Bible,” № 31, Psalm 133

How very good and pleasant it is when kindred live together in unity! —Psalm 133:1

Many years ago, when I was exactly Kalyn’s age, the Wichita Eagle newspaper conducted a survey that identified ten factors people consider when searching for a church home. Prominent among them was a factor identified as “a feeling of belonging, of community.”[1] The experience of those who searched for a church home suggested that such a quality is elusive, not available in every setting. One can be a member of a church, but not experience a feeling of community.

I was so intrigued by this mysterious notion of a feeling of community that it ended up becoming a major focus of my Doctor of Ministry work. In fact, the long title of my thesis starts with the four words: “A feeling of community.” It turns out such a feeling means different things to different people. What prompts the feeling for one may miss the mark completely for another.

When we look at the experience of Christian community in the time of the early Church, we know Jesus’ disciples forged community while facing many difficulties, including persecution from forces outside the church, and conflict from within it. Still, the power of the Risen Christ, and the new force of the Holy Spirit, created such powerful bonds that members of the newly formed church held all things in common, as described by Luke in the Acts of the Apostles.[2] When they were meeting together and eating with glad and generous hearts, I imagine those early church members experienced a feeling of community, and they believed deeply that this was the place they belonged, more than any other.

Someone who has thought deeply about feelings of community is Robert Putnam, who, at age 81, still is listed as an active professor of public policy at Harvard. In his breakout book Bowling Alone, Putnam described the way in which patterns of belonging changed in the recent history of our nation. He showed that many forms of social involvement have shown great decline.

There are, he said, many reasons contributing to this trend. There are pressures of more time spent at work, greater mobility, suburban sprawl, and the influence of technology and mass media. Twenty years ago, and speaking somewhat prophetically, Putnam suggested that churches stand in danger of seeing the load-bearing beams of their infrastructure “hollowed out” by this trend.[3]

But it wasn’t just the structure of ministry that would be jeopardized by less commitment to social engagement. The health of individuals would be impacted, too. Psychologist Martin Seligman, one-time president of the American Psychological Association, argued that rates of depression rose in our country at the same time our commitment to community activities was de-emphasized. He said that an emphasis on personal control and independence may work for a few, but leaves many others unprepared for failure. Where once they could fall back on a network like you find in a community of faith, the connections are no longer there to cushion the fall.[4] When people going through the stresses of pandemics or hurricanes no longer seek shelter in local congregations, where do they turn? I don’t know the answer to that question, but imagine that some of the places like the internet expose them to more danger and offer less support.

Like our country, the nation of Israel went through circular movements of community decline and revitalization. Following the death of Saul, Israel’s first king, there was a period of confusion. This was followed by a great impulse of unity when hearts were drawn together around the newly anointed King David. And after the death of Solomon, the feeling of unity was lost again in fierce divisions between northern and southern tribes, and a long period of strife.

From the time of David, the words of the 133rd Psalm were preserved and venerated.[5] During the division that followed Solomon’s time, it was natural to take up again a song from the golden years of Israel’s power. For the psalm proclaimed, amidst the strife and bloodshed, the truth that had so long been obscured: “How very good and pleasant it is when kindred live together in unity!

The figures of speech that the psalmist uses are simple but beautiful. He chooses first the most fragrant thing used in the worship of his time, comparing the spirit of harmony to the precious oil with which the High Priest was anointed. The psalmist describes the extravagant way in which the oil, when it was poured out, ran down the priest’s beard, over his garment, and diffused itself over his entire person.

From the experience of temple worship, the psalmist moves next to the realm of nature to find another symbol of the beauty of community. This time he compares the spirit of harmony to the dew of Mount Hermon. Especially in the heat of Israel’s summer, the snow-capped peak to the north is a symbol of cool refreshment. The psalmist says that the same moisture which rises from its wooded slopes and deep, snow-filled ravines under the warmth of the summer sun, is carried down to bring water and life to the foothills of Zion. The psalmist says that in this refreshing dew -- the community of God’s people -- “the Lord ordained his blessing, life forevermore.”[6]

What do you think about this psalm? Is there something nurturing and life giving about belonging to the community of God’s people? Or does this psalm merely represent a sentimental wish for unity among those tired of diversity and conflict?

Turning once again to Robert Putnam and the team of researchers that a place like Harvard is able to pay, there is a fair amount of evidence to support the idea that Christian community nurtures health and wholeness. It is not only that belonging to a church gives us a network for finding a helping hand, though that’s important.[7] Even more impressive are the many studies showing that social connectedness is one of the most powerful determinants of health and happiness.

Putnam carefully describes experiments showing that “people who are socially disconnected are between two and five times more likely to die from all causes, compared with matched individuals who have close ties with family, friends, and the community;”[8] and that “the single most common finding from a half century’s research on . . . life satisfaction . . . is that happiness is best predicted by the breadth and depth of one’s social connections.”[9]

Robert Putnam created an index to assess the relative benefits of belonging to one another in close relationships. He says that getting married is the happiness equivalent of quadrupling your income. He says that regular church attendance is the happiness equivalent of getting a college degree or more than doubling your income. He says that regular participation in a small group is so powerful that, if you smoke and belong to no groups, it is a toss-up statistically whether you should stop smoking or start joining.[10] Putnam’s work demonstrates that where people live together in unity, there is life!

For years, I’ve kept an old printout entitled “The Rescuing Hug,”[11] which described the story of twins Kyrie and Brielle Jackson born prematurely at a hospital in Massachusetts. Each one was in her respective incubator, and Brielle was not expected to live. Nurse Gayle Kasparian argued against then-current neonatology rules to place the babies in the same incubator. When finally the twins were placed together, the healthier of the two placed an arm over her sister in a kind of embrace. Almost immediately, the smaller baby’s heart rate stabilized and other vital signs began to improve.

The sisters now are 27 years old. What they experienced in those early days now is known as “the hug that changed medicine.” Their story is one of the of most clear and powerful reminders I can imagine about the truth of today’s text. It’s a text that seems especially relevant on World Communion Sunday, and the day of the annual church picnic. “How very good and pleasant it is when kindred live together in unity . . . . For there, the Lord has ordained … blessing, life forevermore.”

NOTES

[1] Diane Samms Rush, “Church Shopping: Like Wise Consumers, People Just Know What They’re Looking For When They Visit a Congregation,” The Wichita Eagle, 25 June, 1994, sec. C, p. 8, col. 1.

[2] Gospel of Luke 2:42-47.

[3] Robert D. Putnam, “Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community,” New York: Simon & Schuster, 2000, p. 72.

[4] Putnam, pp. 261-265, 335, summarizes Seligman.

[5] Traditionally ascribed to David, the psalm is not easy to date precisely. A date before the Exile is suggested by linguistic analysis in Mitchell Dahood, “Psalms 101-150,” The Anchor Bible vol. 17A, Garden City, NY: Doubleday & Co., 1970, p. 250-253.

[6] In my remarks about the psalmist’s symbolism, I draw heavily from Henry Van Dyke’s “The Story of the Psalms,” Sixth Edition, New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1905, pp. 235-246.

[7] Putnam, p. 20.

[8] Putnam, p. 327.

[9] Putnam, p. 332.

[10] Putnam, p. 331.

[11] https://www.snopes.com/fact-check/rescuing-hug/

READ MORE, https://www.fpcedw.org/blog