Blessed are the Peacemakers

Blessed are the peacemakers, for they will be called children of God. –Matthew 5:9

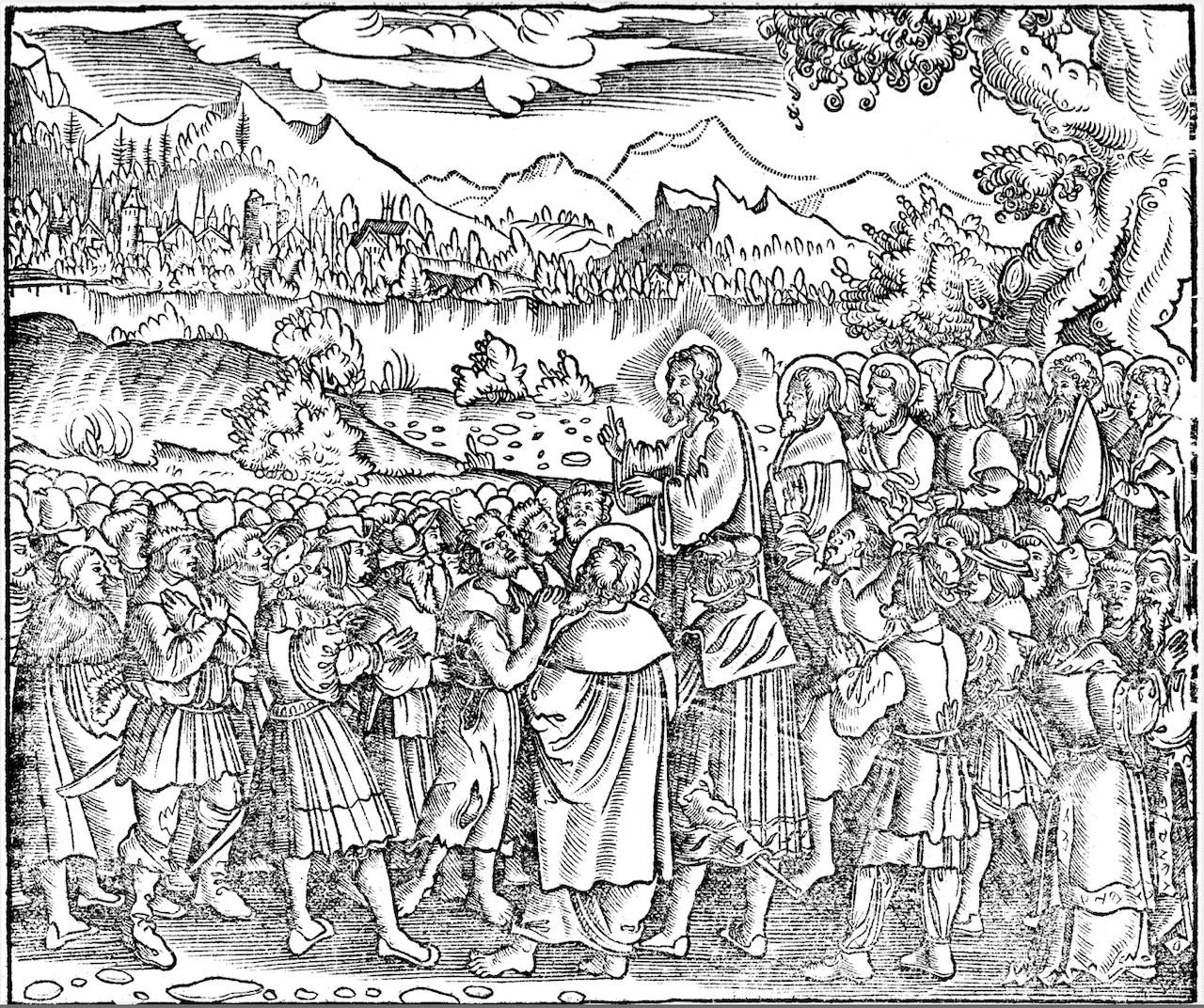

Jesus gathered with his disciples on a gentle slope rising from the northern shore of the Sea of Galilee. From the green countryside, they looked over the tranquil village of Capernaum. It was short walk down the hill to the cool waters of the lake. The lush surroundings, such a contrast to Jerusalem, served to reinforce the difference in his religious vision.

Here, Jesus spoke about the character of those who would live in his kingdom, including the seventh of his so-called Beatitudes, “Blessed are the peacemakers ….” From the same site, just a few days ago, you and I could have seen ballistic missiles streaking across the night sky. I would rather not think about the need for peacemakers. But if preaching is to be faithful, then it’s necessary.

Voltaire, the 18th century philosopher and atheist, hated the Church. Prominent among his reasons was the charge that the Church failed to make peace. “Go through the five or six thousand sermons of (the Pope),” he says. “You will scarcely find one in which a word is uttered against the scourge and crime of war. Miserable physician! Of what concern to me are benevolence, humanity, modesty, temperance, gentleness, wisdom, and piety, so long as half an ounce of lead shatters my body and I die at twenty in torments unspeakable, surrounded by five or six thousand dead or dying, while my eyes, opening for the last time, see the town in which I was born delivered to fire and sword, and the last sounds that reach my ears are the shrieks of women and children expiring in the ruins – and the whole for the glory of some man whom I have never seen?”[1] Whenever the Church forgets its mission of peacemaking, it deserves the stinging rebuke of Voltaire.

We prefer to avoid thinking too much about the pain of human conflict, the horror of war, and the need for peacemaking. But when missiles fall from the sky, bombs explode, and gunfire continues daily in places like Gaza, Lebanon, Israel, and Ukraine, we can’t completely avoid thinking about how Christian faith relates to it. Our annual peacemaking Sunday offers up a good opportunity.

Jesus said, “Blessed are the peacemakers.” That simple statement stands in stark contrast to the world leaders we hear who talk about revenge and retribution. What is a peacemaker? The Greek construction with which Matthew records Jesus’ words is straightforward: a person who brings peace, who actively reconciles parties in conflict. Elsewhere, Jesus tells the disciples to “be at peace with one another.”[2] Paul, in today’s first scripture, advises Christians to “live peaceably with all,”[3] if possible.

What then is the Church to say other than “Violence is bad, and peace is good”? I find some help in theologian Reinhold Niebuhr’s book, “Moral Man, Immoral Society.” Niebuhr says that it is difficult but possible to apply Christ’s teaching to personal ethics. It is possible to be a “moral man.” But, he argues, it is more difficult to apply Christ’s teaching to public ethics. While individuals are independent moral agents capable of defining a sense of right and wrong, large groups of people compose what Niebuhr calls a complex “immoral society.” Working toward the public good necessarily involves looking out for the complex interests of many, and making compromises, which is messy business that never can offer a perfect solution for each and every individual.

As this distinction applies to today’s text, peacemaking has social dimensions, and personal dimensions. On the one hand, none of here probably feels we have power to influence the vast “immoral society.” You and I may feel there’s not much we can do about missiles falling in Israel, Gaza, or Ukraine, that we have little power to influence leaders who feel that aggressive war-making is the way to go. On the other hand, each of us has power to act morally to change our corner of the world. Many small acts of peacemaking add up to make a powerful difference.

Timothy Ciciora is an honorably retired Command Master Chief, a senior enlisted leader in the United States Navy. He writes about his struggle with anger and depression following the first Gulf War, following more than twelve years of service. When his ship returned, he wanted no accolades or honors. He was tired and mad at the world. He was sick of hype, sick of the unpredictability, sick of being away from family. He just wanted to go home.

On an overnight road trip to visit his parents, at dawn he pulled up in Chattanooga, and turned into a Burger King to find breakfast. A young woman stepped up to the cash register, took his order, and returned with his food.

Just as Tim was pulling cash from his wallet, the young woman looked over his uniform, and said timidly, “Excuse me, did you just get back from the war?”

“Yeah,” he grumbled, thrusting a twenty at her. Civilians always ask the same questions, he thought. “Are you a Navy Seal?” “Did you kill anybody?” He didn’t want to hear it, and wasn’t in the mood for small talk.

The young woman didn’t take offense at his rudeness. Instead, she gently rolled his fingers back around the twenty-dollar bill. Leaning over the counter, she planted a kiss on his knuckle, and looked up into his eyes as if memorizing his face. Then she spoke one word: “Thanks.” Tim says that he had to get out of there because his anger melted away in tears.

He remembers it a milestone that changed his life. He writes, “Here was this kid who had no ulterior motive, no agenda … yet she bought my breakfast …. Her register would probably come up short … and she’d have to make up for it out of her own pocket …. Unlike (others) supporting the war (as if) some sort of fad, this young lady’s gesture came from the heart …. This sudden, unexpected expression of thanks from a total stranger hit me like a lightning bolt …. Nothing could compare to the simple tribute she’d given me. It made me remember why I was here. It renewed my faith.”[4] This encounter worked out the way it did because a single person chose to act in a way that brought peace to someone else.

If the daily news makes you too pessimistic, please remember that we, too, can be peacemakers, changing the world one person at a time. We are peacemakers when our own hearts and minds are at peace. We are peacemakers when we approach conflict with heartfelt concern and a listening ear. We are peacemakers when we handle conflict by expressing our own position rather than insulting another’s position. We are peacemakers when we seek agreement on the things that are essential, but compromise on things that are optional. We are peacemakers when we offer support, rather than open new wounds. That support may be most noble when offered while we ourselves are hurting. This is what Jesus did when, dying on the cross, he blessed his enemies. Today, he says to us, “Blessed are the peacemakers, for they shall be called children of God.”

NOTES

[1] As recorded by F. W. Boreham, “The Olive Branch,” in “The Heavenly Octave,” New York: The Abingdon Press, 1936.

[2] Mark 9:50.

[3] Romans 12:18.

[4] Timothy Ciciora, “The Homecoming,” in “The Right Words at the Right Time, Volume 2: Your Turn,” ed. Marlo Thomas. New York: Atria Books, 2006, pp. 6-7.

READ MORE, https://www.fpcedw.org/pastors-blog